About a year ago, we introduced our colleague Jan Kaufman, the leader of the Laser Shock Peening (LSP) team, as part of the Meet HiLASIANs series. During the interview, he mentioned that he teaches at the Dolní Břežany Elementary School. We recently had the opportunity to watch his Life is Science class and interview him about it.

How did it happen that you started teaching at the school?

A few years ago, the management of the Dolní Břežany Elementary School decided that they would like to incorporate a science class taught by staff members of the ELI and HiLASE laser centers into their regular curriculum. The idea was that since we already have these centres here in Břežany, we could somehow connect it with teaching and let real scientists bring the world of science closer to the children in a more entertaining way, since children are sometimes quite sceptical about science subjects such as mathematics or physics. Initially, more scientists were rotated in the classes, but over time it turned out that this method is not very good, because the children had to get used to someone new every time and the classes lacked a longer-term concept. So eventually, I offered to teach all the classes.

Why this particular subject?

The subject of Life is Science is a perfect fit considering the laser centres. With my qualifications and experience, I design my classes more along the lines of physics and mathematics. Eventually, I would like to dive deeper into chemistry or biology, but physics is close to me and I am able to prepare high-quality lessons.

What do you like about teaching children?

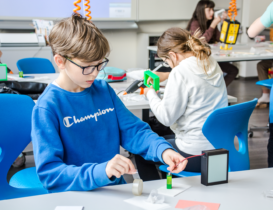

I think it is not at all easy to engage younger children these days. Thanks to the internet, they’ve seen a lot of things and a lot of things are just boring to them. However, it’s not impossible, and if the lesson is successful in such a way that the children are excited and enjoy it, then I’m very happy about it and I think that’s why I’m doing it.

Teaching in primary school requires a lot of patience and very often, form wins over content.

And what is it that you do not enjoy so much about teaching?

When I spend a lot of time preparing a lesson and the kids don’t enjoy it at all, they are bored and would rather be on their phones doing nothing. Of course, it’s also my fault that the lesson might not have been engaging enough. I’m just finding out gradually what works and what doesn’t. It also varies a lot from class to class. I also get very frustrated when I have a few kids in my class who are downright ruining it for the others with their attitude and disrupt the lesson a lot.

What is it like preparing for a lesson compared to preparing a lecture for, say, International Day of Light or an excursion?

There’s quite a big difference because you usually get people coming to your lectures who are already interested in the topic beforehand, so you’re talking to kindred spirits. At the same time, this audience tends to be older on average as well, so you can build the whole thing right around that interesting topic. With the sixth and seventh graders I teach, you can have any topic you want, but if you don’t deliver it in a fun way to those kids, you’re going to fail and the whole thing will fall apart. So lessons with kids require a lot more preparation time, which can be challenging for me sometimes because I have my regular job and other hobbies on top of that. However, successful lessons can then be recycled the following year, so that need for lots of preparation gradually decreases.

Do you feel that as a scientist, you have a “duty” to pass on your knowledge?

I certainly don’t think of it as a “duty”, but it’s something that fulfills me in a way. I think all of us can still remember that one teacher or that we had a lot of fun with as kids and it stuck with us to this day. Stuck with us in a good way, of course. I am so grateful to these former great teachers of mine and, who knows, maybe I’ll be teaching their children now, and I can repay them at least a little. I think staying a motivated teacher long term is very difficult and those who can do it have my respect. Plus, I really enjoy the interaction with the kids, so it’s kind of mutually rewarding.

How do you perceive the motivation of children and aspiring young scientists? Does it even make sense to introduce school-age children to the scientific environment?

I’d almost say when else to start introducing science? I don’t count on the kids memorising a lot of information in the traditional sense. It’s more about leaving them with a positive impression, so that maybe in the future they won’t be afraid of science and maybe even pursue that direction. If they enjoy it, of course.

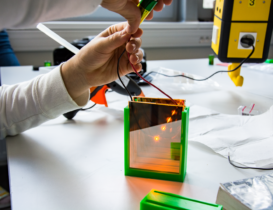

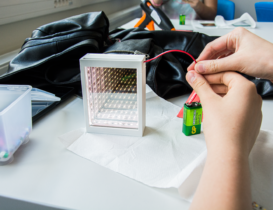

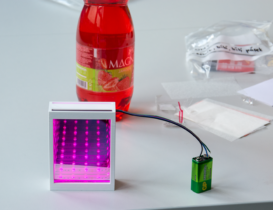

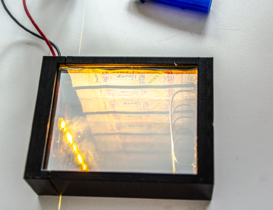

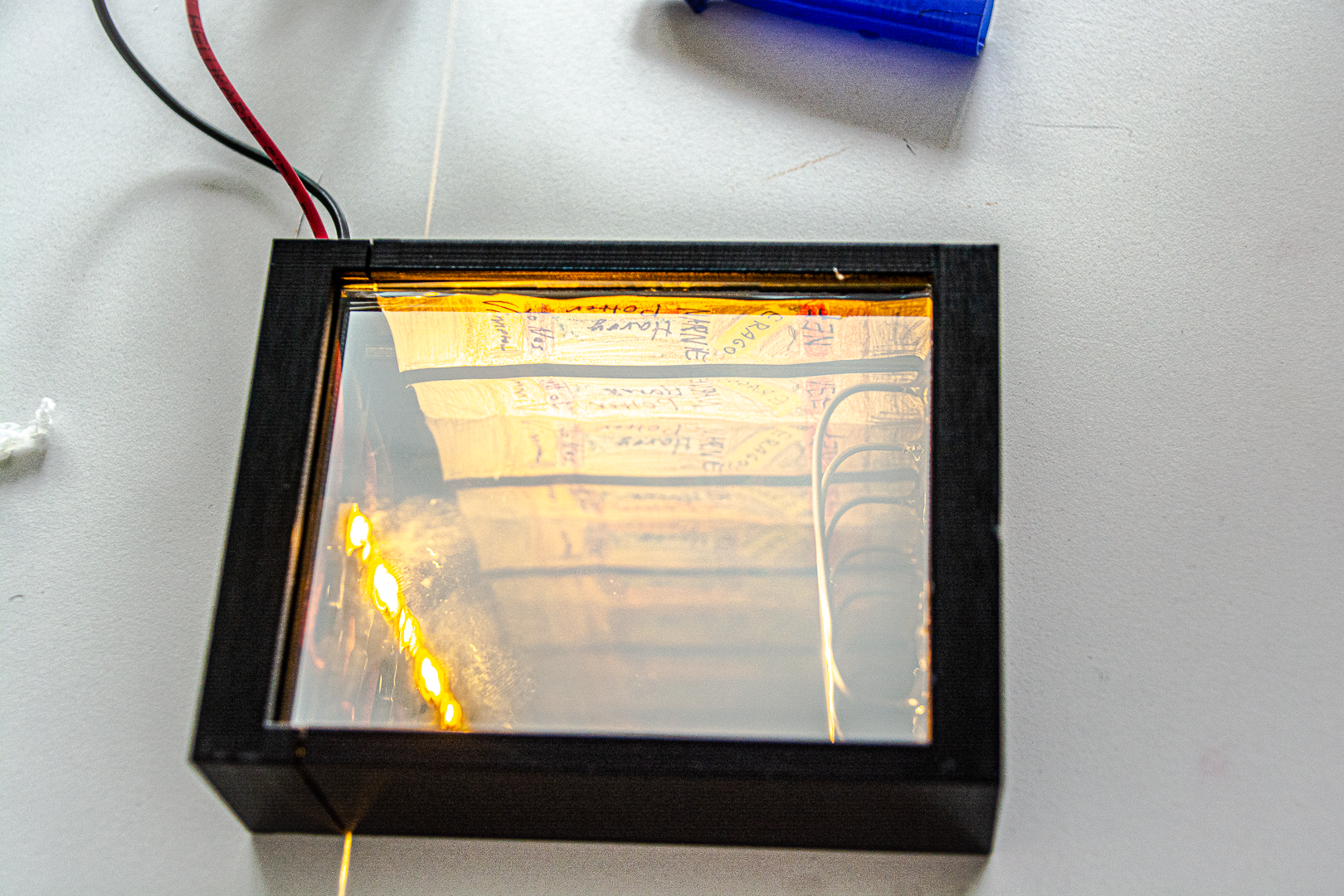

You just did an infinity mirror experiment. I was surprised at the enthusiasm with which some of the students created their mirrors. I noticed that you had prepared a “personal” packet for each of them with the necessary tools and materials, as well as wishing them to succeed in making the mirror. Do you think you could share a brief explanation of how the infinity mirror works with us?

An infinity mirror is a concept that uses 2 plane mirrors that are placed parallel to each other. The rear mirror is a classic mirror that we know from the bathroom, for example. The trick is the front mirror, which is semi-transparent. So it still reflects light, but you can see through it. We can see such a mirror in films, for example, during a police interrogation, when the person being interrogated is in a room with a large mirror on one wall. Behind this mirror the interrogators stand and can observe the interrogated person, while he cannot see the interrogators. The whole thing works because the space on one side of the semi-transparent mirror is highly illuminated, while the other side is low-lit. You can see this in the film as well, the interrogators are mostly standing behind the mirror in the dark, while the room with the interrogatee is well lit. We will replace this light in our experiment with intense light from diodes or a diode strip. We then act as interrogators ourselves, looking in from the outside through a semi-transparent mirror. The rear mirror in this arrangement then causes the space between the mirrors to copy many times as the light rays are reflected between the two mirrors. The result is the illusion of infinite space in between the mirrors.

Is there anything you would say to all primary school pupils?

It’s hard to tell these kids something like this, because it’s usually things they have to figure out on their own. But there is one thing I would say. If they are interested in something or have an idea, they shouldn’t be shy and they should go to their favourite teacher. The teacher will then be happy to guide them further so that they can explore their interest more and maybe even make it happen. There is nothing to be afraid of, on the contrary, personal initiative is very much appreciated, at least by me.

Is there anything you would say to scientists who are starting to teach at a school like you are?

Teaching in primary school requires a lot of patience and very often, form wins over the content. As I said before, in the beginning, there were more of us taking turns in these classes. Some colleagues tried it once and then never again because it just wasn’t for them. At the same time, I would add that what you make of it is what you get. I’m sure there are more distinctive ways to go about it, so why not try?